The Rise of DuckDuckGo

Date: December 9, 2019Category: Author: David Hall

To stay abreast of what is going on with search, we subscribe to a number of services from Search Engine News, including their monthly podcast updates. In one of those podcasts earlier this year, they announced that they were going to now be including update reports on the search engine DuckDuckGo, added to their reports on Google and occasional updates on Bing. Last January, DuckDuckGo reached the milestone of 1 billion search queries per month, which is what prompted the policy change.

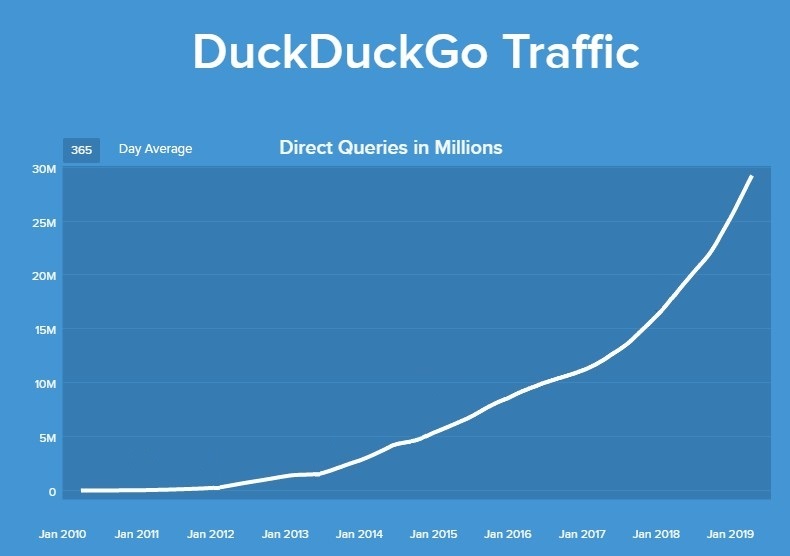

The reason DuckDuckGo is attracting more attention lately isn’t so much their search volume—they are still getting only about 1% of search traffic in the United States. It’s their momentum. They are showing sustained geometric growth. Bing gets about 4% of search traffic in the United States, but their volume growth isn’t dramatic. DuckDuckGo has had serious geometric growth since it was launched in 2008.

There is also significant buzz about DuckDuckGo. A week ago, they received a warm endorsement from Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey who tweeted:

“I love @DuckDuckGo. My default search engine for a while now. The app is even better!”

– Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey

They are also attracting attention because of their policies. Their primary marketing pitch is privacy. They don’t store data on users the way Google does. Here is how they put it:

- We don’t collect, store, or share your personal information, Ever.

- We don’t follow you around with ads. We don’t store your search history. We therefore have nothing to sell to advertisers that track you across the Internet.

- We don’t track you in or out of private browsing mode. Other search engines track your searches even when you’re in private browsing mode. We don’t track you—period.

But there are growing rumblings in the public about another issue, manipulation of search results by Google, something that DuckDuckGo doesn’t do. In September I published a blog post about Google’s new policy of filtering search results. Let me give here a quick summary. When Google started, I had been doing search engine optimization for a couple of years. They gradually overtook the position of being the leading search engine because people came to see that they got better results with Google. Their strategy at the time was to measure the number and quality of links pointing to a particular page to determine the value of that page. It was a democratic system. Google has now switched to a more authoritarian model. For example, they have introduced into their algorithms a concept they call “algorithmic unfairness.” Here’s an excerpt from one of their internal documents:

“Definition: ‘algorithmic unfairness’ means unjust or prejudicial treatment of people that is related to sensitive characteristics such as race, income, sexual orientation, or gender through algorithmic systems or algorithmically aided decision-making.”

Later in that document it expands on that definition as follows:

“For example, imagine that a Google image query for ‘CEOs’ shows predominantly men . . . Even if it were a factually accurate representation of the world, it would be algorithmic unfairness because it would reinforce a stereotype about the role of women in leadership positions.”

DuckDuckGo, on the other hand, doesn’t do any such filtering of their results. Here is what that difference means, with a couple of examples.

I have transformed my original private practice dental website into a general website about cosmetic dentistry in which I continue to answer questions from the public and recommend some cosmetic dentists around the country. In the past, this website enjoyed very high rankings in google, but for some inscrutable reason recently has been seriously downgraded by them, a casualty of the Panda, Penguin, and most recently the “Medic” update. It is actually more authoritative than the vast majority of websites about dentistry. Anyway, two years ago I was contacted through that blog by one Chip Halbauer. He told me he was looking for a way to give his father, Dr. Stewart Halbauer, proper credit as the real inventor of the Maryland Bridge. I asked him for the full story, so he emailed me back. He told me how his father had a patient who needed a tooth replaced but didn’t want a conventional bridge. So his father came up with the idea of attaching a false tooth to metal wings and bonding it to the adjacent teeth. This patient subsequently moved to Maryland where he became the patient of Dr. Livaditis, a member of the faculty of the University of Maryland. Seeing this successful winged bridge, Dr. Livaditis and his partner Dr. Thompson tweaked the design and published a research paper about it. I found Chip Halbauer’s story highly credible and so edited the page about the Maryland Bridge on my website to give his father credit as the inventor and wrote a blog post about how I learned this.

So I thought I would compare Google with DuckDuckGo and Bing on how they answered the question, “Who invented the Maryland Bridge?” To answer this question, Google pulls an instant answer snippet from the website of Dr. Livaditis at the University of Maryland who, interestingly, doesn’t claim to be the inventor of the Maryland Bridge, only the co-developer with a Dr. Thompson. However, if you ask either DuckDuckGo or Bing this same question, they draw their instant answer snippet from mynewsmile.com and give the correct answer. This is an example of how Google’s authoritative model breaks down and gets in the way of delivering an accurate answer to the question.

There are many other examples. Political searches are heavily filtered. Try some of them and you’ll see what I mean. Some scandals are sanitized. Not that long ago, The New York Times was criticized for some anti-Semitism in their editorial department, a criticism that brings back haunting old memories of The New York Times burying stories about the holocaust that were coming out of Nazi Germany. Understand that Google treats The New York Times as one of its premier authority websites and so I think it is fair to assume that they want to defend them. If you Google “New York Times anti-Semitism,” the top six results are all The New York Times preaching to us about not being anti-Semitic. You don’t learn about their own scandal until near the bottom of the page. However, if you search on DuckDuckGo, half of the first page has results about the scandal with the first mention of it at position three. On Bing, seven out of the ten results on the first page accuse the Times of having an anti-Semitism problem. Numerous other searches reveal a pattern of favorites that Google has as well as websites or causes it doesn’t like.

Watching traffic for the websites we manage, this year over last year, traffic coming from DuckDuckGo has doubled or tripled. Traffic from Bing is also up about 40 to 50%. For websites that Google seems to have unfairly targeted, traffic from DuckDuckGo is somewhere just above 8% of search traffic while Bing traffic is about 14%. For sites that are doing well in Google the traffic is more like about 3-4% for Bing, 1% for DuckDuckGo. My opinion is that the competition is healthy and will work to bring the best results for the user, as opposed to the best results according to some outcome that is determined by a monopoly search engine. For me, I still monitor Google results closely for business purposes, but for my own personal use, while I still use Google for image and maps searches, I tend to use both Bing and DuckDuckGo for text searches, with Bing as my default search engine.

Informative to the point I will change my personal search engine to DuckDuckGo.